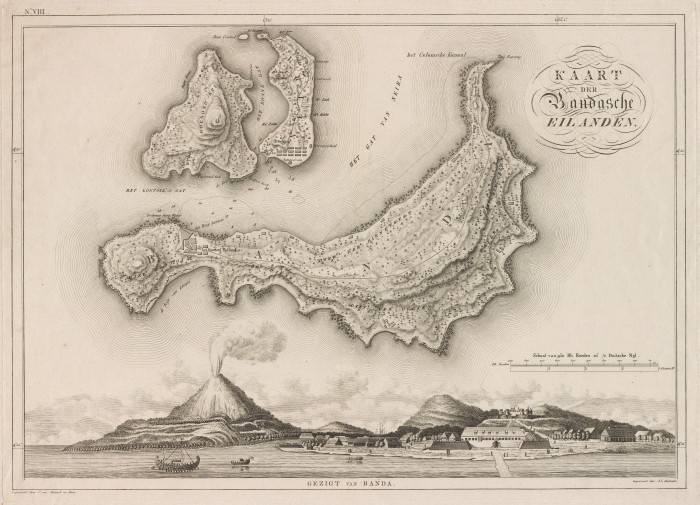

When we talk about Banda, we are actually talking about the Banda Islands, a collection of islands – Neira, Lontor, Rosengain, Pisang, Gunung Api, Keraka, Ay, Nailaka, Run and Manukang. These days Rosengain is called Pulau Hatta, and Pisang has been named after Syahrir, the first vice-president and prime minister respectively of independent Indonesia. Both were in exile on Neira for many years in the 1930s.

The Banda Islands in a nutshell

Ron Habiboe and Wim Manuhutu

Map of the Banda Islands

The Banda Islands are located in the Banda Sea. With a maximum depth of 7,440 metres, it is one of the deepest seas in the world. The Banda Sea is directly connected to the Pacific Ocean. As in other parts of the Moluccas, the rainy season on the Banda Islands runs from June through October. During this period, the weather is characterised by strong winds that make the waters around the islands difficult to navigate. Only large ships are able to sail from Ambon in the north to the Banda Islands, a journey that takes eleven hours. In the dry season, smaller, faster ships also sail, taking over six hours.

the fire mountain

The average temperature on the Banda Islands is 28 degrees Celsius. In the months of November through March, the temperature can rise another few degrees.

The islands were largely formed by volcanic activity. This is not surprising as they are located in the so-called Banda Arc where different tectonic plates meet. Earthquakes and seaquakes are a recurring phenomenon on the Banda Islands.

One of the islands, Gunung Api (literally: fire mountain) still has an active volcano rising over six hundred metres above sea level. As recorded in various historical sources, Gunung Api has erupted more than twenty times in recent centuries, with major consequences for nature and people. The last big eruption was in 1988. For the inhabitants of the islands, the question is not if there will be another volcanic eruption, but when.

As a result of its historical origins and the location of the islands, the south of Neira Island offers more shelter from the sea winds, which has allowed it to develop into a natural port over time.

The combination of volcanic soil and their location made the Banda Islands ideal for the nutmeg tree (Myristica fragrans), which produces nutmeg and mace. As highlighted in other contributions (for example of Roy Ellen), the inhabitants of the Banda Islands increasingly specialised in the cultivation of nutmeg and mace well before the arrival of Europeans. And they actively participated in regional and long-distance trade networks through which the region – Seram, Ambon, Kei and Aru – supplied the Banda Islands with sago, fruit and vessels.

Map of the Gunung Api by Johannes Vingboons (coll. National Library of Austria)

first settlements

For traces of the first human habitation of the Banda Islands, we depend on archaeology. Fortunately, regular research has been conducted on the Banda Islands in recent decades, and it demonstrates human presence on the Banda Islands more than seven thousand years ago,

The discovery of Chinese ceramics dating from the fifth century is proof of the existence of ancient trade contacts with the outside world. And like other islands in the Moluccas, there seems to be a distinction between communities that had more contact with that same outside world and communities that were more isolated and not located near easily accessible landing sites. Archaeological research shows that, from the thirteenth century onwards, the influence of Islam can be seen in the form of food consumption and burial rituals. The consumption of pork and the cremation of the deceased continued into the sixteenth century.

How did the Bandanese perceive themselves and the world around them? As far as we know, the voices of the Bandanese are heard only sporadically in written European sources. And there are no manuscripts written by them either, or at least these are not publicly accessible.

On the other hand, there are other sources too that can be consulted.

oral tradition and the story of Boi Ratan

The Moluccas have always had an oral tradition: stories were handed down orally. Some of these were considered to be just stories and others were historical stories. These old stories have been known among the native population for a very long time. The historical stories are considered original and bearers of truth.

One of these stories tells of a Bandanese princess Boi Ratan and her unifying role for a large part of the Moluccas. There are several local variations of this story. We first present a general version here.

In the past, the islands of Seram, Ambon, Saparua, Haruku, Nusalaut and Banda in the Central Moluccas formed one large island. One of the rulers there was the Raja of Lautaka, who had seven sons and one daughter. One of his slaves was the son of the great ruler of Sahulau, another Raja on the big island. This slave fell in love with Boi Ratan, the daughter of the Raja of Lautaka. His love was reciprocated and they had a son together. However, before their child was born the slave, the son of the Raja of Sahulau, fled.

When Boi Ratan’s child was born and Boi Ratan did not disclose who the father was, her seven brothers accused each other. A trial by ordeal was to bring a solution. A circle was drawn in the sand and the child was placed in the centre. The brothers squatted around the circle. Whomever the child would crawl to, that would be the father. However, the child crawled out of the circle without going to any of the brothers. So the child was not fathered by any of the brothers. Who the real father was, remained unknown. In any case it did not seem to be a man of royal blood. Out of shame, Boi Ratan was expelled from her home. She left to seek her lover, the father of her child.

At the time, the father of Boi Ratan’s child had returned to Sahulau and in the meantime he had succeeded his father as Raja Sahulau. However, when Boi Ratan reached Sahulau, she was rejected by her former lover, the Raja of Sahulau. Although Boi Ratan was indeed a princess, the daughter of an independent ruler, her father was no equal to the rulers of Ternate, Djailolo, Batjan and Sahulau, according to her former lover. It was with great sadness that Boi Ratan left Sahulau with her child. She cried, not because she had been expelled from her own father’s house or because she would not be the princess of Sahulau. She was sad because she had given her love to someone who was not worthy of it.

Map of the Moluccas

The creation of the islands of Seram, Ambon, Haruku, Saparua, Nusalaut and Banda

So far the different versions of the story of Boi Ratan are generally similar. What happened to Boi Ratan after this point can differ in content and in details in different cases. The version from the village Amahai on Seram, for instance, relates that the father of Boi Ratan’s daughter, who is also the son of the Raja of Sahulau, bears the name Hasimilalu. This Hasimilalu is said to have possessed a magic knife, given to him by his mother, during his stay with the Raja of Lautaka. The knife was called Sima-Sima and could create springs, rivers, seas and islands. When Hasimilalu fled from Lautaka, he had accidentally left the knife Sima-Sima behind. Boi Ratan had taken this knife with her on her journey to Sahulau.

After Boi Ratan and her daughter Boi Heka were sent away from Sahulau, she embarked on a long and tiring journey. In the end, she was so tired that she sat down on the ground, started to lament and stuck the knife Sima-Sima into the ground. This caused a piece of land to break off and drift away, forming the island of Ambon. After this, she carved figurines of herself and Boi Heka and stuck the Sima-Sima into the ground again. The ground of Seram, which had come loose, drifted away with the figurines. Thus the islands of Haruku, Saparua and Nusalaut came into being. She then put Boi Heka on the ground, and with her tears and her lament she lastly created the Banda Sea and the Banda Islands. What ultimately happened to Boi Ratan and her child is unclear. In different versions, both disappear from the world, they fade into nothingness. This version of the story of Boi Ratan is important for the Central Moluccas because it connects the islands of Banda, Ambon and the Ambonese Islands (Lease Islands) with the large mother island of Seram.

Bandanese spread out

The many different local versions of the story of the fate of Boi Ratan and her child after they were expelled from Sahulau often connect different family clans in the Moluccas with Bandanese ancestry. For example, the version from the village of Amahusu on the island of Ambon. Much of the story of Boi Ratan corresponds to the general version quoted above. However, the Amahusu version starts with the fact that once upon a time there was a king in Banda named Lawataka. Together with his wife Mulika Nyaira Banda Toka, he had not eight but seven children, including a daughter called Boi Ratan. After the story of her being pregnant with a son instead of a daughter, the trial by ordeal, the journey to Sahulau, the rejection and expulsion from Sahulau, Amahusu’s version tells us that Boi Ratan left Seram in a small sailing boat. After some wandering, Boi Ratan landed on the south coast of the island of Ambon where she went ashore. She settled in a place that later became the village of Amahusu. During one of the wars, the people were tired and thirsty. So Boi Ratan’s son stuck his spear into a rock and then water came out of the crevices of that rock. Afterwards, the people recognized Boi Ratan’s son, whose name was Boikiki, as king of the village Amahusu. He was given the surname Silooi, after the carrier basket his mother had when she became pregnant. According to this version, the Silooi family has descended therefore directly from Boi Ratan, the princess from Banda.

In various places in the Moluccas, outside the Banda Islands, there are numerous families who refer to Bandanese origins. These histories are often recorded in so-called kapata, histories handed down orally, often in the form of a (sung) poem. Also Banda’s old name, Wakan or Wakang, which recurs in clan names, names of the ancestors, or names of old settlements, points to a Bandanese background. However, in many cases it is unclear when these Bandanese families or groups settled in the villages concerned. Was it prior to the depopulation of the Banda Islands, or right during those violent years of 1609-1621?

View on Banda in: Van den Bosch, Atlas der Overzeesche Bezittingen (coll. Atlas van Stolk Rotterdam)

Neira

Apparently there were several towns on the island of Neira before the arrival of the Dutch in Banda. There was the populous capital Labetaka on the north coast, which also ruled the three villages Lactor (Lacija), Gioe (Gioul) and Lucra. On the south coast there was Neira, which also had three towns under its control, namely Oerien (Ower), Sjak (Kijac) and Ratoe (Rato). A cultural and political division ran through much of the Moluccas. It divided them into the faction of the league of five (ulilima) and the faction of the league of nine (ulisiwa). A village or community belonged to the one of the other faction. Not infrequently, there was hostility between the factions. Until around 1598, towns on the island of Neira already belonged to the so-called league-of-five faction (ulilima). Around that year, Labetaka and its three dependent villages switched to the league of nine (ulisiwa). Neira and its villages, until that moment more powerful and richer than Labetaka, were regularly at war with those of Labetaka . During the violence with the VOC of the early seventeenth century, all of these towns were destroyed and virtually no physical traces of the villages remained, except for the name Labetaka, which lived on in the name of one of the later plantations, the so-called ‘perken’. And in the vicinity of the former Ratoe, many Muslim graves and tombstones were the only reminders of the earlier presence of Bandanese Muslims. As it later turned out, some Bandanese women remained, who by then had become Christians and who still told their children every day that the graves were haunted.

Photo by Lookman Alibaba Ang

Lonthoir, Bandan

Across from the island of Neira was the larger, elongated island of Bandan, which the Dutch would later called Lontor, after the town that had been there on the northwestern coast from time immemorial. This town was also responsible for the villages Mandiange (Mandiangijn) and Luksoy (Lacaij). In addition there was the village of Gammer (Sammer), which was divided into four kampongs and which had the village of Woena (Wontera) under it. On the north coast was the village of Ortattan, also known as Orontatte (Orantatten). The name was derived from the Malay word orang datang (the people are coming) because from this village or from a somewhat higher spot one could see foreign vessels arriving further away in the sea. In the years 1550-1560, this was to be one of the largest and most important trading posts. These six towns all belonged to the faction of the league of five (ulilima).

Also on Bandan Island, on the northeast side were the villages of Kombir (Comber) and Reai Rane, or also called Ranan (Rauijen). Next to it, on a hill, was the old village of Selamon (Salamme). In 1590 the village of Ranan was still part of this village, although it actually belonged to Kombir. On the eastern side of the island were the villages Oudendender (Ouwendender) and Wayer (Waijer). This latter village had two more villages under it: Bogton (Botton) and Oeman (Reben?). These four and three more unknown villages were all committed to the faction of the league of nine (ulisiwa). So there were at least sixteen towns or villages on the whole island of Bandan. The village of Ortattan was always neutral in times of war. There, the ulilima and the ulisiwa factions convened under a large sacred tree. A low stone wall had been built around this tree and the space inside was filled with earth. Above it sat the so-called orang kaya, the heads of the towns and villages. Meetings used to be held here twice a week: on Tuesday and Saturday.

Photo by Lookman Alibaba Ang

Gunung Api, Pulau Ay, Rhun en Rosengain

To the west of Neira lies the island of Gunung Api, Fire Mountain. The story in the early seventeenth century was that in ancient times there were many villages on the beach, but due to several volcanic eruptions, everything had been destroyed; even the names of the villages had been forgotten. The fourth island is Pulau Ay (Island of Ay). In old times there were two towns here, namely Timor and Vrat (Ourat). The latter town was divided into Upper Vrat and Lower Vrat. They all belonged to the ulilimas.

In ancient times Run island had the towns of Varaat and Toeldam (Toubedin). The inhabitants belonged to the ulilimas and, together with the inhabitants of Ay, considered themselves masters of the four towns on Neira. They felt this way because their ancestors had first settled on the islands of Ay and Run and, after planting many kinds of fruit trees there, at some point travelled to Neira, where they left some of their people behind to take care of their business. Thus, around 1600, the inhabitants on Neira still owed mooring fees and other taxes to the inhabitants of Ay and Run.

Finally, the smaller island Rosengain, also called Rosingein. There were three villages here: Woetra (Wutera), Tanamassa (Taramasta) and Vali (Ratta?) which fell under a Raja of Rosengain. And in 1590, this Raja, together with the leaders kapitan Falat, kapitan Atijauh, orang kaya Watimena and their people from the other villages of Banda, went to Ambon to help the Muslims on the Hitu peninsula in their fight against the Portuguese, Christians and infidels. After several victories, their fleet returned to Banda.

size of the Bandanese population

Around the year 1600, there were about 31 villages in total on the Banda Islands. The size of the Bandanese population is unknown, but the total population of the six traditionally inhabited Banda Islands has been estimated at 15,000 souls, including about four to five thousand able-bodied, armed men.

Photos by C. Dietrich, around 1880, from a photobook from the collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Literature

Ellen, Roy, Beyond the Banda Zone (Honolulu 2003)

Fraassen, Chr. Van, de Negenbond en de Vijfbond, appendix XII, in: Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipelago (dissertation Leiden 1987), pp. 460-462.

Heringa, G., Amboina Ambon (ICCAN without date)

Jansen, H.J., “Ethnographische bijzonderheden van enkele Ambonsche negorijen”], Bijdragen tot de taal-. Land- en volkenkunde (BKI), vol.98 (1939), pp. 325-368.

Lape, Peter, Historic Maps and Archaeology as a Means of Understanding Late Precolonial Settlement in the Banda Islands, Indonesia, in: Asian Perspectives, Spring 2002, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Spring 2002), pp. 43-70

Leupe, P.A., “Beschrijvinge van de eijlanden Banda” BKI, vol.3 (1855), pp. 73-105

Lilipaly-de Voogt, Ada, De boom vol schatten (Utrecht/Zuidwolde 1993).

Manusama, Zacharias Jozef, ‘Hikayat Tanah Hitu’ (Dissertation Rijksuniversiteit Leiden 1977).

Straver, Hans, De Zee van verhalen (Utrecht 1993).

Valentijn, François, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën, IIIb (photomechanical reprint Franeker 2003).